One Wednesday lunchtime in January 1971, they came for Rubens Paiva, barging into his beachfront home in Rio and taking him away – to an unknown location.

Marcelo Rubens Paiva, the son of the engineer and politician, was just 11 years old at the time. He recalls the terrifying feeling of not knowing what would happen next, especially when his sister and mother were arrested the following day.

After a brief and harrowing stay in a torture center operated by Brazil’s military dictatorship, Paiva’s female relatives were eventually released. However, his 41-year-old father never returned. It took 25 years for authorities to acknowledge his murder, and Paiva’s remains were never found.

The abduction and murder of Rubens Paiva, a high-profile crime during the 1964-85 regime, is depicted in a new successful film by director Walter Salles, starring Fernanda Montenegro.

Marcelo Rubens Paiva, son of Rubens Paiva, attends the I’m Still Here red carpet during the Venice International Film Festival on 1 September. Photograph: Stefania D’Alessandro/WireImage

Based on Marcelo Rubens Paiva’s book of the same title, „I’m Still Here“ has resonated with many in a country still grappling with the aftermath of its dictatorship. The film has been watched by nearly 2 million people since its release in early November, leading to a surge in the popularity of Paiva’s book published in 2015.

Quick GuideBrazil’s dictatorship 1964-1985Show

How did it begin?

The leftist president of Brazil, João Goulart, was overthrown in a coup in April 1964, leading to General Humberto Castelo Branco assuming power and initiating 21 years of military rule.

The repression intensified under Castelo Branco’s successor, Artur da Costa e Silva, who implemented a decree granting him dictatorial powers and ushering in a period of tyranny and violence known as the “years of lead” until 1974.

What happened during the dictatorship?

Supporters of Brazil’s military regime credit it with bringing security and stability, as well as overseeing economic growth. However, the regime also engaged in violence and repression, including the murder and torture of its opponents.

It was a time of severe censorship, leading many prominent figures to go into exile.

How did it end?

Political exiles began returning in 1979 after an amnesty law was passed, paving the way for democracy. The “Diretas Já” movement in 1984 played a crucial role in transitioning to civilian rule.

Thank you for your feedback.

The release of the film coincided with a federal police report revealing a potential plot to return to military rule in Brazil just two years ago.

The report alleges that former president Jair Bolsonaro, a staunch supporter of the dictatorship, was involved in a conspiracy to seize power after losing the 2022 election. Bolsonaro denies these allegations.

Marcelo Rubens Paiva expressed concern over the lack of accountability for past injustices, highlighting the ongoing threat to democracy in Brazil.

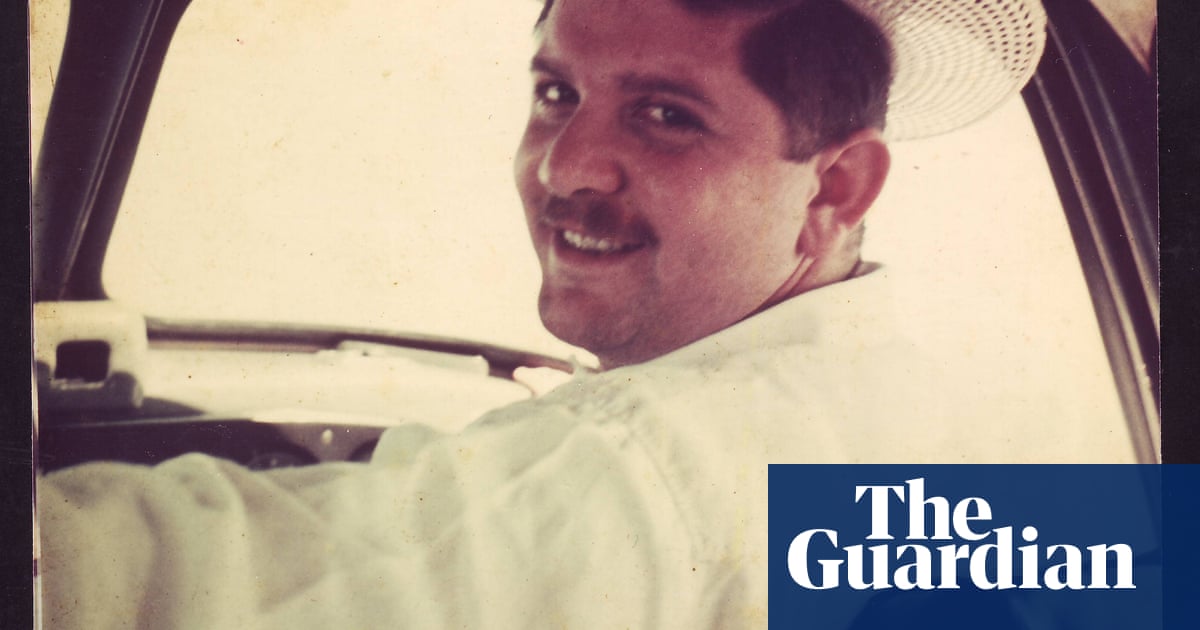

Rubens Paiva, a civil engineer and politician in Brazil, was murdered by the military dictatorship in Brazil in 1971. Photograph: Family handout

Individuals accused of involvement with Bolsonaro in the alleged conspiracy have ties to the 1964 regime, raising further concerns. The film by Salles portrays the impact of political madness on families like the Paivas.

Paiva recalls his father as a jovial figure, whose political career was cut short by the dictatorship. Before his abduction, Rubens Paiva would discreetly meet with foreign correspondents to share information about the regime’s abuses.

Paiva emphasizes that his father was not part of the armed resistance against the dictatorship, shedding light on the repressive climate of the early 1970s in Brazil.

Dennoch wurde er aus seinem Zuhause gerissen und am nächsten Tag zu Tode geprügelt.

Paivas Verschwinden zerstört das häusliche Glück, das in den ersten Momenten des Films dargestellt wird, und bereitet ein Drama vor, das sowohl zutiefst brasilianisch als auch auf unheimliche Weise universell ist.

Der Soundtrack des Films enthält Lieder von legendären Komponisten, von denen einige von der Diktatur inhaftiert oder ins Exil gezwungen wurden, wie Tom Zé und Caetano Veloso. Aber die erschütternde Darstellung einer Familie, die von den ideologisch motivierten Fantasien eines autoritären Regimes zerstört wird, ruft ähnliche Tragödien hervor, die sich fortsetzen, von Peking bis Caracas. „Was in China passiert, passiert in der Ukraine. Es passiert jetzt in Venezuela. Es passiert überall“, sagte Paiva.

Schauspielerin Fernanda Torres in einer Szene aus dem Film I’m Still Here, inszeniert von Walter Salles. Fotografie: AP

Nach dem erzwungenen Verschwinden von Rubens Paiva rückt seine Frau – gespielt von der Schauspielerin und Schriftstellerin Fernanda Torres – in den Mittelpunkt, kämpft darum, ihre Kinder vor dem Horror zu schützen, der sich ereignet hat, während sie nach Antworten über einen Ehemann sucht, den sie nicht betrauern kann. Torres‘ ergreifende Darstellung von Eunices Kampf hat zu Forderungen geführt, ihr den Oscar für die beste Schauspielerin 2025 zu verleihen.

Paiva dachte, der Erfolg des Films sei teilweise durch einen Durst nach Informationen über die Diktatur bei jungen Brasilianern zu erklären, die nach der Rückkehr der Demokratie geboren wurden. Er erinnerte sich daran, ähnliche Szenen in Deutschland Anfang der 90er Jahre erlebt zu haben, als das Publikum die Kinos füllte, um Steven Spielbergs Schindlers Liste zu sehen. „Meine [deutschen] Freunde sagten zu mir: ‚Meine Eltern haben nicht darüber gesprochen. Meine Großeltern haben nicht darüber gesprochen.‘ Es war eine Generation, die entdeckte, was in ihrem Land passiert war.“

Paiva glaubt, dass die Wiederwahl von Donald Trump – der geschworen hat, am „ersten Tag“ seiner Präsidentschaft ein Diktator zu sein – den brasilianischen Film noch relevanter gemacht hat. „Ich glaube, die Leute haben Angst. Jetzt erst recht mit Trump“, sagte er. „Die Welt ist zu etwas geworden, was wir [dachten, dass wir es] bereits hinter uns gelassen hatten.“